Before Thoreau:

Formerly enslaved residents of Walden Woods before Thoreau’s experiment

Starting at the end of the American Revolution and before Thoreau began his experiment living deliberately off the land, Walden Woods was home to a population of free Black residents. Town officials designated Walden Woods as a place in Concord where formerly enslaved people could reside. The land surrounding the Pond was dry and dusty, making it difficult to grow crops and sustain a livelihood. It was common for former slaves to remain in Concord after they obtained freedom, because they had a better chance of maintaining their freedom if they lived near people who knew them. Therefore, formerly enslaved people tolerated Walden Woods’ infertility and remoteness, creating a free Black community that lasted forty years, from approximately 1780 to 1820. In chapter 14 of Walden, Thoreau writes, “For human society I was obliged to conjure up the former occupants of these woods.” Thoreau begins this chapter by sharing stories about the people who lived in Walden Woods before he arrived in 1845.

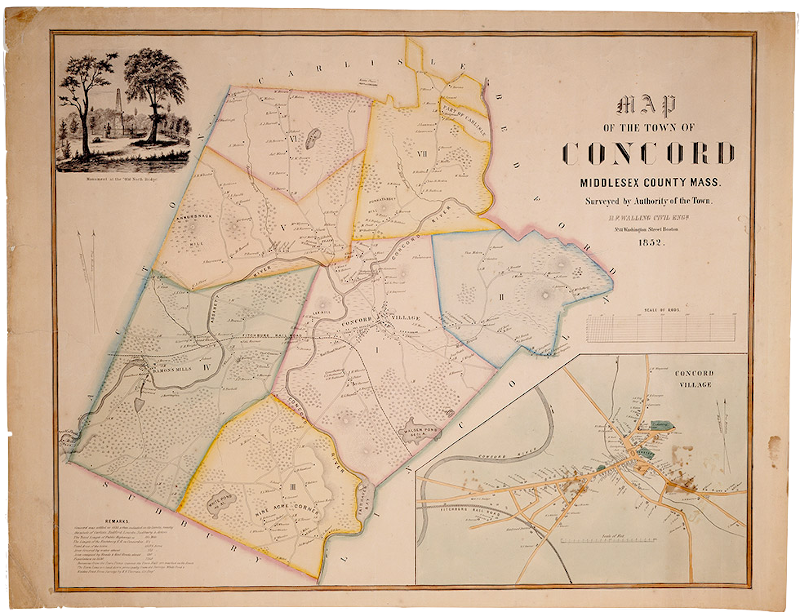

Click to enlarge the map to the right for a close-up view of Concord at the time of Thoreau’s writings:

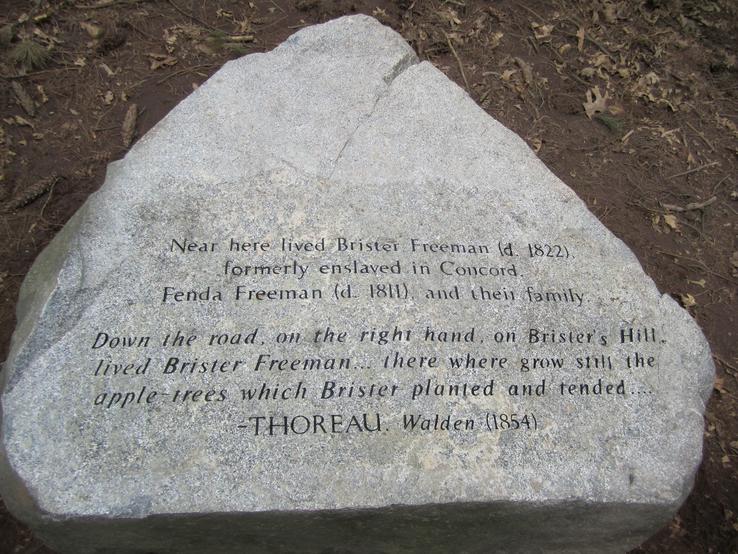

Brister Freeman was the second formerly enslaved person to own land in Concord. Brister’s Hill is named after the area where he and another formerly enslaved person purchased an acre of land. To make a living, Brister worked as a day laborer, and his wife Fenda told fortunes. Both Brister and Fenda were often harassed by local residents and Thoreau was impressed by all that Brister was able to accomplish in such harsh conditions. Thoreau was also impressed by the life Brister and Fenda had made living in Walden Woods, and wrote about walking through the remnants of Bristers’s orchards that still existed during his time in the Woods.

Down the road, on the right hand, on Brister’s Hill, lived Brister Freeman, “a handy Negro,” slave of Squire Cummings once, — there where grow still the apple trees which Brister planted and tended; large old trees now, but their fruit still wild and ciderish to my taste.

Thoreau

In commemoration of his life, in 2011 the Robbins House placed a boulder marking the Freeman Family home site. Source: robbinshouse.org

Zilpah White, sister of Brister Freeman, spent over 40 years living on her own in Walden Woods. Zilpah relied on the skills she had learned while enslaved, and spun raw cotton, wool, and flax into thread and linens to sell in town. Zilpah lived in a one room cabin, quite like the cabin Thoreau later built and lived in. Both Zilpah and Thoreau used their one room cabins for many purposes. They cooked, ate, worked, and slept in their single room. In Walden, Thoreau notes that, like other formerly enslaved persons, she too was harassed. He describes her living conditions as “somewhat inhumane.” And yet her ability to provide for herself at a time when few if any other Concord women lived alone was a great accomplishment.

It is clear that Thoreau was captivated by the lives that these former residents created for themselves in Walden Woods and designed his experiment to closely resemble their experiences with the land.

Here, by the very corner of my field, still nearer to town, Zilpha, a colored woman, had her little house, where she spun linen for the townsfolk, making the Walden Woods ring with her shrill singing, for she had a loud and notable voice.

Thoreau

Cite this page › Chicago Style

Gallo, Travis. “Before Thoreau: Formerly enslaved residents of Walden Woods before Thoreau’s experiment.” The Enslaved Naturalist. John Mitchell, Jr. Program for History, Justice, & Race: Digital Museum. November 1, 2021. [this-url]