Tubman: a “Woman of Earth”

Tubman became deeply acquainted with two of the most significant components to Maryland’s natural environment, which was water and forests.

Tubman was a naturalist, an expert of nature, science, geography, and the physical environment, in several ways. She utilized her knowledge of the physical environment and different components of the natural world to her advantage in leading many people to freedom over the years. For example, she created a number of natural remedies for medicinal purposes, such as a medley of honey and alcohol spirits.

Dr. Iris Barnes, Maryland Commission on African American History and Culture [0:34]

and Ranger Angela Crenshaw, Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park [0:50]

and the descendants of Tubman: Pauline Copes Johnson conversing with Rita Daniels [0:45]

Enslavement overtime gave Tubman “tremendous literacies” about the specifics of Maryland’s landscape, giving her a knowledge base that would aid her personal escape and her future rescue missions that would one day help a multitude of others. Tubman used owl calls to signal coded messages to nearby enslaved people in the forest, sang spiritual songs with changed tempos next to slave quarters, hid undercover in several marshes and other natural plants on Maryland’s shore, and navigated her way North by not just the North Star but by reading the entire night sky:

Pauline Copes Johnson, great-great-grandniece of Harriet Tubman [0:38]

Pauline Copes Johnson conversing with Rita Daniels [0:32]

The poem “Runagate Runagate” by Robert Hayden celebrates Tubman as the “woman of earth” who “mean[s] to be free”.3 Additionally, Tubman used physical skills learned as an enslaved naturalist to help others survive once reaching freedom. She helped chop wood and forage the forest for food and subsistence, as basic needs while hiding from enslavers in the antebellum period were food, water, and shelter. These small examples demonstrate that Tubman had to own, retain, and utilize her “tremendous literacies” of the natural environment about animals, berries, nuts, forests, water, streams, marshes, astronomy, and the like to conduct at least 11 successful rescue missions.

Read Hayden’s poem at poetryfoundation.org

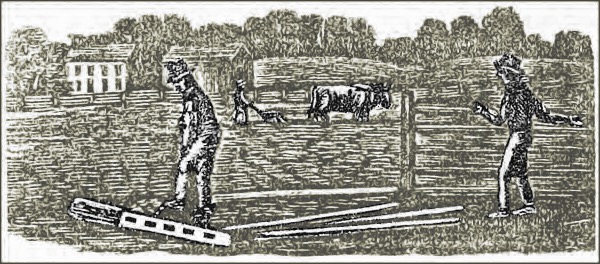

Woodcut depicting agricultural work in antebellum Maryland, c.1855. (Image has been modified for artistic effect.) Source: Hagers-Town Town and Country Almanack by John Gruber. Courtesy of Maryland State Archives Special Collections.

Tubman’s early childhood and adolescence while enslaved on Maryland’s Eastern Shore significantly built and sharpened her physical and survival skills that she relied upon later in her life when she was free. Though Tubman moved around and worked on different plantations over the years, she remained on the shores of Maryland for most of her adolescent life until she ran away in 1849.

Chris Haley, Director of the Maryland State Archive’s Study of the Legacy of Slavery in Maryland [1:18]

Throughout her enslavement, Tubman performed a variety of tasks on Maryland’s Eastern shore. She trapped muskrats, was hired out as a nurse, hired out as a housemaid, helped build a canal, and later hired herself out to plow fields and haul timber with a team of oxen.4 All of these jobs helped Tubman build skills that were expanded on when she escaped slavery and found freedom. For one, the labor required for tasks such as building a canal and plowing fields built physical strength that later aided Tubman in multiple lengthy rescue missions. Secondly, Tubman learned “tremendous literacies” about the landscape of Maryland from these jobs.

Ranger Angela Crenshaw [0:43]

Ranger Angela Crenshaw [0:41]

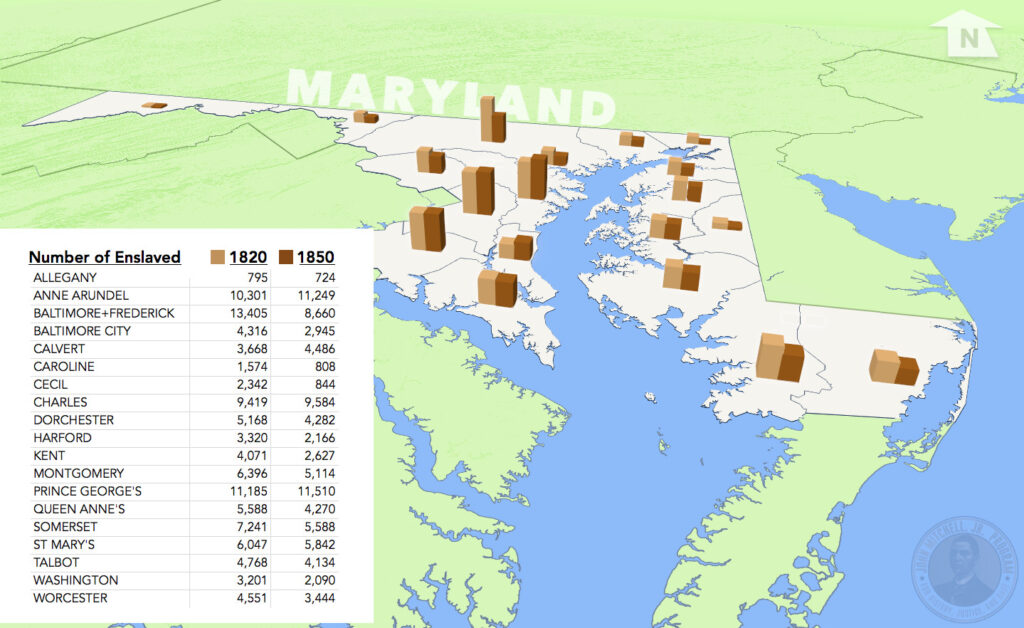

For instance, Tubman became deeply acquainted with two of the most significant components to Maryland’s natural environment, which was water and forests, from trapping muskrats and hauling timber. In the mid-19th century, Maryland consisted of a number of marshes, rivers, and forests, which also provided substantial cover for enslaved runaways.

The geography of Tubman’s Underground Railroad routes. Inset photos: National Park Service

Tubman was sometimes confident enough to move about during the day in pursuit of food and information, as she ‘had confidential friends all along the road’ who could be trusted to help her, while her companions stayed safely secreted in the woods.”5 Tubman participated in and created a reliable network of communication and “friends along the road” when she helped build the Stewart Canal in Maryland. This job not only brought her closer to Tobacco Stick plantation, reuniting her with family and friends, but it also allowed her to participate in a vibrant African American community.

Though less physical, Tubman would draw on her prior enslaved jobs as a housemaid and nurse later in life. Once free, she worked as a housemaid in Philadelphia while dodging re-enslavement and was also working as a nurse (while being a spy) during the Civil War:

Conversation with Rita Daniels [1:03]

Dr. Iris Barnes [1:00]

All of these examples showcase how Tubman used her past enslaved labor to her advantage and refashioned the physical skills and work experiences learned in her adolescence on the Maryland shore for her own purposes of emancipation and survival.

Ranger Angela Crenshaw [0:51]

3 Kate Clifford Larson, Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman: Portrait of an American Hero (New York: Random House, 2004), 102.

4 Larson 57, 78, 83.

5 Larson 117.

Cite this page › Chicago Style

Brannan, Laura. “Tubman: a ‘Woman of Earth’.” The Enslaved Naturalist. John Mitchell, Jr. Program for History, Justice, & Race: Digital Museum. November 1, 2021. [this-url]