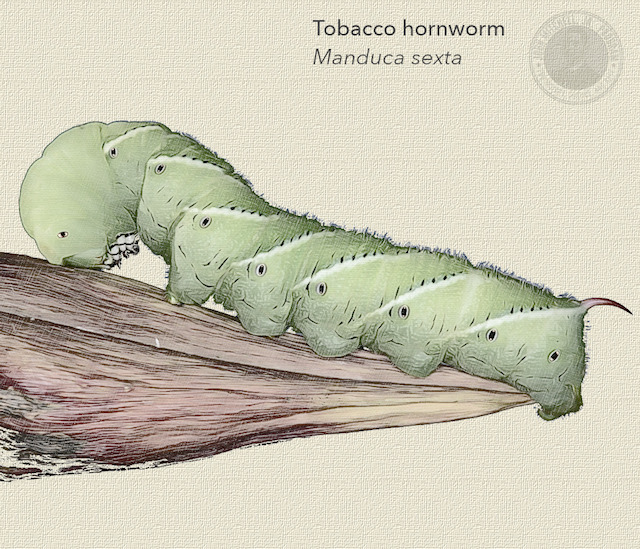

The Lewis and Clark expedition described at least 178 plants and 122 animals. While no plants or animals bear York’s name, like the Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana) or the Lewis woodpecker (Melanerpes lewis), it is clear that he helped identify many of the species that were documented along the way. On March 7, 1806, Lewis stated “a bird of a scarlet colour as large as a common pheasant with a long tail has returned, one of them was seen today near the fort by Capt. Clark’s black man.” Likewise on July 14th, 1806, Clark wrote: “Saw a Tobaco worm shown me by York.” The former was likely a red phase ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) and the latter probably a Tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta).

March 7, 1806

a bird of a scarlet colour as large as a common pheasant with a long tail has returned, one of them was seen today near the fort by Capt. Clark’s black man, I could not obtain a view of it myself.

—Meriwether Lewis’ journal

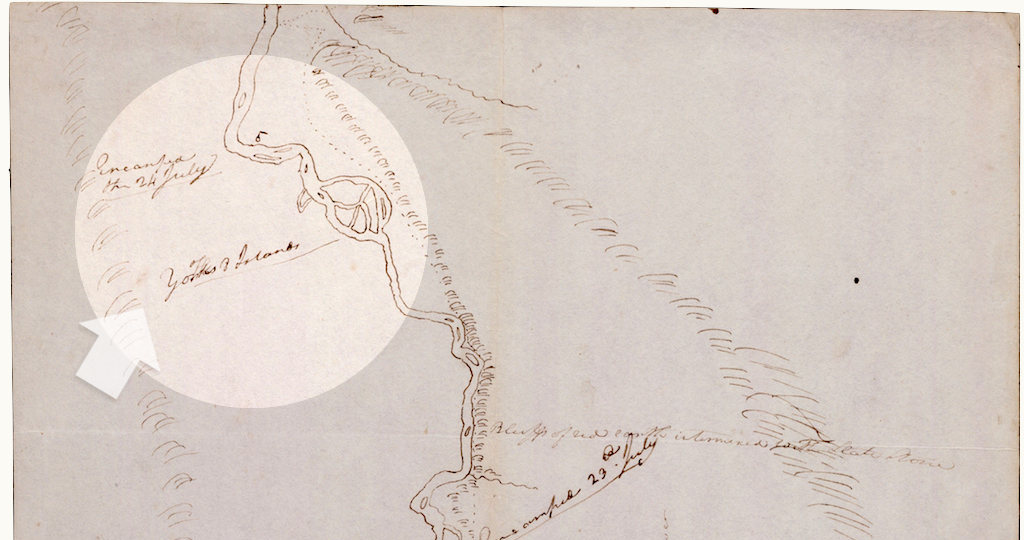

The expedition’s geographical findings were also significant, and Clark often chose York to accompany him as he surveyed canyons, streams, and rivers. On July 24, 1805, Lewis described, in detail, the scene of many beavers and other wildlife along an area of the Missouri River that was characterized by many small islands. Clark would later name this area “Yorks 8 Islands” on his survey maps. This is one of two locations that Clark named after York. The other was a tributary of the Yellowstone River which Clark named “Yorks Dry Creek.”

The need for Clark to name these geographical areas after York, offers some indication that York’s contribution to discovering or surveying these areas was significant to Clark.

Wednesday July 24th, 1805

we saw many beaver and some otter today; the former dam up the small channels of the river between the islands and compell the river in these parts to make other channels; which as soon as it has effected that which was stoped by the beaver becomes dry and is filled up with mud sand gravel and drift wood. … thus the river in many places among the clusters of islands is constantly changing the direction of such sluices as the beaver are capable of stoping or of 20 yds. in width. this anamal in that way I beleive to be very instrumental in adding to the number of islands with which we find the river crouded.

—Meriwether Lewis’ journal

While the Lewis and Clark Expedition was meant as a diplomatic and economic journey, it became a well-documented expedition of scientific discovery that significantly advanced our ecological and geographical understanding of the continent. And York, an enslaved man, was there playing a major role in these discoveries.

After the Expedition

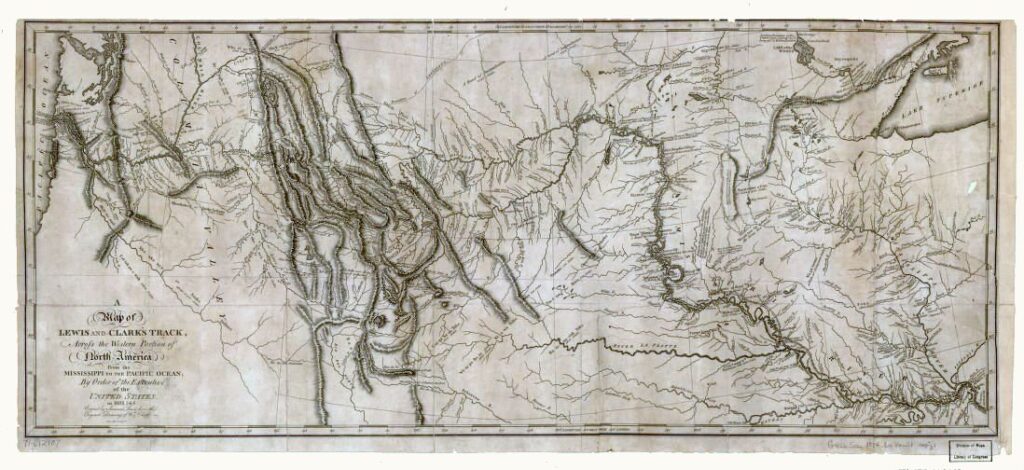

Expanse of the map area relative to the United States’ territory in 1804:

When the Corps of Discovery returned from their expedition, York was not freed for his service, but instead Clark insisted on keeping him enslaved. A reminder that York did not volunteer to participate in the Expedition, but was in fact an enslaved man the whole time.

York was well aware of the national fame that the Expedition had gained — and for his essential contributions to the success of the mission. He requested to be freed in return for his service, but Clark denied his first request for freedom.

“I did wish to do well by him. But as he got Such a notion about freedom and his emence Services…I do not think with him, that his Services has been So great/or my Situation would promit me to liberate him.”

—William Clark, 1808

York was finally released from William Clark’s bondage sometime after 1815. Little is known about York after he was free. Clark told the author Washington Irving that York had started a hauling business, but that his business had failed. However, Zenas Leonard, a fur trapper in the 1830s, recalled meeting a Black man living among the Crow people in Wyoming saying “the man claimed he first came into that territory with Lewis and Clark.”

York did not receive a just reward for his contributions to the Expedition. However, now is the time to acknowledge his place as an early naturalist and a major contributor to our understanding of natural history in the United States.

Cite this page › Chicago Style

Chavis, Charles, Jr. and Travis Gallo. “York, the Naturalist.” The Enslaved Naturalist. John Mitchell, Jr. Program for History, Justice, & Race: Digital Museum. November 1, 2021. [this-url]