Conclusion

On suppressed and contested histories

Throughout the history of the United States, the contributions of people of African descent have been suppressed to further a false narrative. The fields of conservation and natural history are no exception. Likewise it is easy to relegate historical figures (of any background or artificial category of people) into neatly-defined boxes. African African naturalists—in this exhibit, Harriett Tubman, York, and the Black residents of Walden Pond—prove that such boxes are overwhelmingly limiting.

At the same time, and not coincidentally, Black people have been historically excluded (deliberately and very often aggressively) from enjoying natural spaces, from feeling safe in public places, and from thinking of the land as their own.

The gross injustice and dehumanizing status of enslavement did not, in fact, stamp out any of these naturalists’ contributions. Ranger Angela Crenshaw of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park points out that the legacy of exclusion can also be overcome:

Ranger Angela Crenshaw [1:21]

This exhibit aims to promote narrative change by introducing learners of every age and background to the complex and expansive contributions that enslaved African Americans have made in the United States. This exhibit is informed by a recent wave of others, too, that have sought to salvage their unheard, forgotten, and overlooked voices. Today there are many movements, both inside and outside the official institutions of government, that are looking now to honor the contributions of historical figures such as Tubman, York, and the historic African American communities across the United States.

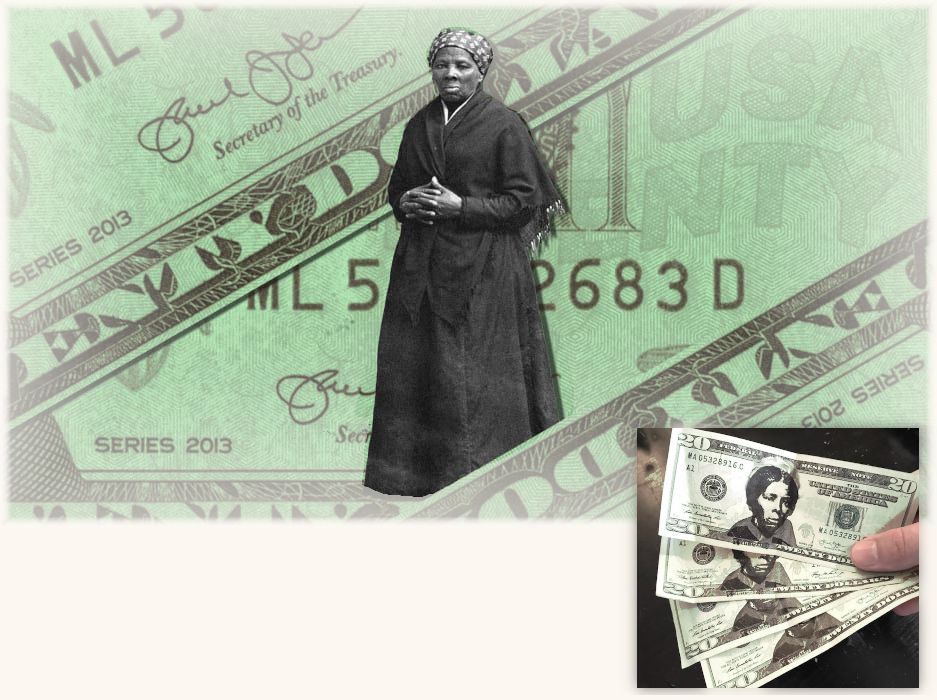

For example, in 2016, Pauline Copes Johnson—the great-great-grandniece of Harriet Tubman—wrote a letter to Secretary of the Treasury Jack Lew, and the Treasury Department’s subsequent decision to put Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill, replacing Andrew Jackson, was met with mixed responses from political leaders and the public. The original goal was to release the new bill in 2020, on the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the United States. However, the project was delayed during the Trump Administration after the history of our nation was politicized. This did not stop Tubman’s many fans from developing and sharing their own 3D-printed rubber stamps, so that anyone could imprint her face over Jackson’s in a guerrilla-style art project.

Amid a global pandemic and racial reckoning in the U.S., protests in Portland, Oregon, emerged in October 2020 in response to the continued practice of police brutality towards people of color in the United States. As a result, a statue of Harvey Scott, a prominent white editor of a 19th-century newspaper, was toppled in Mount Tabor Park. This was a part of an ongoing movement calling for the removal of statues honoring men, women, and others who contributed to the systemic oppression of ethnic minorities in the United States.

Following the removal of Scott’s statue, the space remained empty for about four months. Then during the last weekend in February 2021, a four-foot bust of York was mysteriously erected atop the granite pedestal that once featured Scott.

The sculptor remained anonymous, but left a comment: “[The statue] pays homage to York at a time when we all need to remember the important role that African Americans have played in our history and reflect on the tragedy of slavery—a tragedy that continues to echo.” Unfortunately, this sculpture did not remain long, as it was toppled in July of 2021 by suspected white supremacists.

The sculptor of this statute provides a fitting perspective regarding the importance of historiography (how we approach learning history). For students and educators alike, the John Mitchell, Jr. Program hopes that this exhibit will allow us to reflect on the injustices and triumphs of the past, that we may strive to learn from both the positive and negative elements of our nation’s history. Through exhibits such as this, visitors might honor the lived experiences of enslaved African Americans and learn from this history as we seek to build and sustain a peaceful future for all of humanity and our environment.

See also:

Cite this page › Chicago Style

Chavis, Charles, Jr. “Conclusion: On suppressed and contested histories.” The Enslaved Naturalist. John Mitchell, Jr. Program for History, Justice, & Race: Digital Museum. November 1, 2021. [this-url]

Previous Next