The Robbins House:

Antislavery, environmental justice, and Thoreau

The Robbins House was a small 540 square foot house, built in the early 1820s, and located on a small farm overlooking the Concord River. The first families that lived in the house were descendants of the Revolutionary War Patriot, Caesar Robbins. In 1823, Caesar’s son Peter Robbins purchased the house and over 13 acres for $260 – “an accomplishment so rare that every neighbor can point to him. I doubt if there are three such

men in Concord,” as Thoreau wrote about Peter.

Peter and his wife Fatima resided in the west side of the house; Peter’s sister, Susan, her husband Jack Garrison, and their children occupied the east side. Peter Hutchinson, Fatima’s relative, bought the house in 1852. He and his large family were the last to live in this house on the farm.

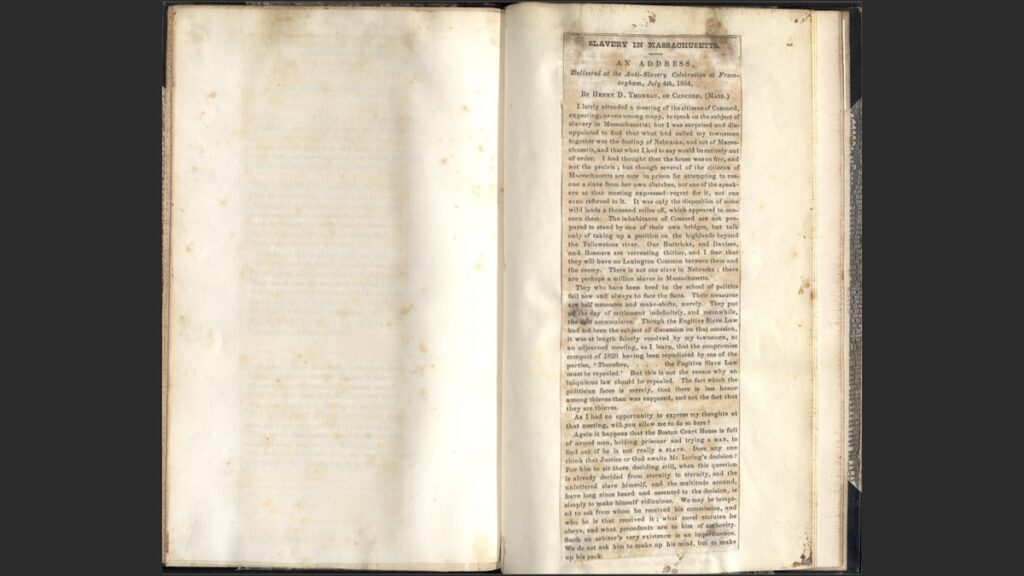

By sharing a house and land, several early Concord African American families were able to support themselves and live independent lives. Several occupants of the Robbins house were antislavery activists and abolitionists that were influential characters in Concord during Thoreau’s time. Thoreau decried a system that accepted human bondage and saw the exploitation of people and of nature as two sides of the same coin of injustice. In “Slavery in Massachusetts,”

he wrote the following: “[W]hat signifies the beauty of nature when men are base?”

Thoreau was an abolitionist and an environmentalist and began to recognize environmental injustices in his writings. While he does not write as much about the Robbins residents, they were influential like-minded neighbors and likely influenced his thoughts on these topics.

Source: Harvard Library

Susan Garrison and her husband Jack Garrison lived in the Robbins house from 1823–1837. Susan was a charter member of the Concord Female Antislavery Society (CFAS). In 1837, she hosted the second CFAS meeting in her home. Susan is the only woman of color listed in existing CFAS records. As the daughter and wife of previously enslaved men, Susan signed petitions against slavery, the slave trade, and the removal of the Cherokees from their homeland in the southeastern United States.

Ellen Garrison, the daughter of Susan Garrison, spent her life educating newly freed people and advocating for their civil rights. Born and raised in the Robbins house, Ellen’s followed in her mother’s footsteps as an antislavery activist. At 12, she marched in a Concord parade hand-in-hand with her white schoolmate and signed many petitions as a way to make her voice heard. After the Civil War, Ellen taught newly freed people during Reconstruction.

Peter Hutchinson was a distant relative of Caesar Robinson and the last person to live in the Robbins house. Peter “had more local knowledge of woodlots and meadow bounds than any man in town,” according to J.S. Keyes, a lawyer and lifelong resident of Concord. Peter constructed buildings, slaughtered livestock, and sold pigs to other farmers. He won first prize in the plowing contest at the 1835 Middlesex agricultural fair.

The stories of the occupants of The Robbins House reveal the ways in which the first generations of free Concord African Americans pursued independence and contributed to the antislavery movement. Similar to the Dugans, Thoreau writes of his opportunistic encounters with the Robbins House occupants. For example, while out botanizing in July 1852, Peter Robbins informs him that a heavy storm the day before had not ruined their potato crop, as had been feared—”exorbitant potatoes!” writes Thoreau. In 1854, Peter Hutchinson tells Thoreau about seeing gulls and sheldrakes flying over the Great Meadow.

In these and similar instances, Thoreau’s neighbors are just fellow naturalists, sharing observations of the natural world around them.

It is not too far a leap to think that these residents informed his personal views on slavery and environmental justice.

Image above: Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Concord, MA, in April 2010. Photo by John Phelan, CC-BY-3.0

Cite this page › Chicago Style

Gallo, Travis. “The Robbins House: Antislavery, environmental justice, and Thoreau.” The Enslaved Naturalist. John Mitchell, Jr. Program for History, Justice, & Race: Digital Museum. November 1, 2021. [this-url]