Although York had no say in the decision, at 30-something years old he was chosen to accompany the “Corps of Discovery” on their expedition from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark conferred at length about who would accompany them on their expedition. They chose interpreters, soldiers, and French oarsmen who were familiar with the western United States. They also chose York.

York became a skilled hunter and was often put in charge of hunting and foraging responsibilities. It was unusual that an enslaved person was allowed to handle a gun, but York’s contribution proved too valuable to maintain the standard practices of slavery. York was the primary caretaker for ill soldiers, and at one point he risked his life to save Clark, Sacagawea, and her son when they were caught in a flash flood.

June 5, 1804

…

York Swam to the Is[lan]d. to pick greens, and Swam back with his greens

—William Clark’s journal

November 16, 1805

…

York killed 2 geese and 8 Brant, 3 of them white with a part of their wings black and much larger than the Grey brant which is a Sise larger than a Duck.

—William Clark’s journal

York also possessed considerable skills as a trader and diplomat with Native Americans that would salvage the mission and the lives of the corps members. These members possessed a freedom that he never realized. Indeed, Clark and others downplayed York’s trading skills, suggesting instead that York somewhat enchanted Native Americans. This hyper-emphasis on black exoticism downplays the contributions made by York, who, contrary to western history, was not the only “Black” mountain man to have worked closely with Native American communities during this era.

…McNeal and york were sent on a trading voyage over the river this morning. having exhausted all our merchandize we are obliged to have recourse to every subterfuge in order to prepare in the most ample manner in our power to meet that wretched portion of our journy, the Rocky Mountain. …Our traders McNeal and York were furnished with the buttons which Capt. C. and myself cut off our coats, some eye water and Basilicon which we made for that purpose and some Phials and small tin boxes which I had brought out with Phosphorus. in the evening they returned with about bushels of roots and some bread having made a successfull voyage, not much less pleasing to us than the return of a good cargo to an East India Merchant.

—Meriwether Lewis2

It was not all adventure for York. Clark used him as entertainment—to impress Native Americans—and often ridiculed him in public settings by making him dance like a buffoon or act like a monster. These stories stand as a stark reminder that while York’s contributions were invaluable, he was never given recognition of his full humanity as an enslaved person.

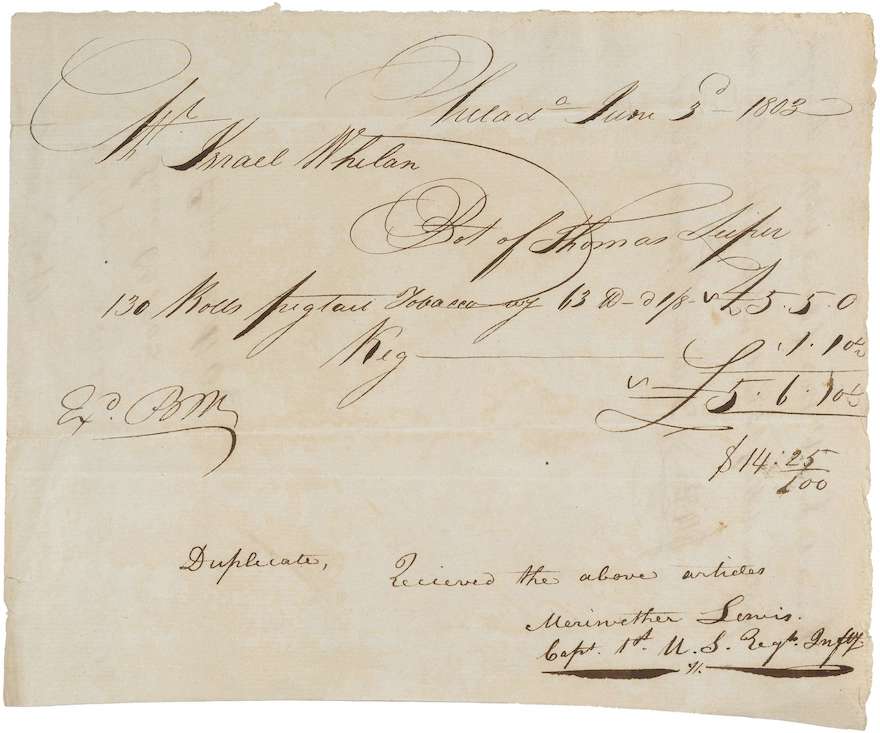

2 Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, et al., June 2, 1806 entry in The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, ed. Gary Moulton (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press / University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries-Electronic Text Center, 2005), https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1806-06-02#n35060208

Cite this page › Chicago Style

Chavis, Charles, Jr. and Travis Gallo. “York as Big Medicine: Tradesmen, Diplomat, and Hunter.” The Enslaved Naturalist. John Mitchell, Jr. Program for History, Justice, & Race: Digital Museum. November 1, 2021. [this-url]