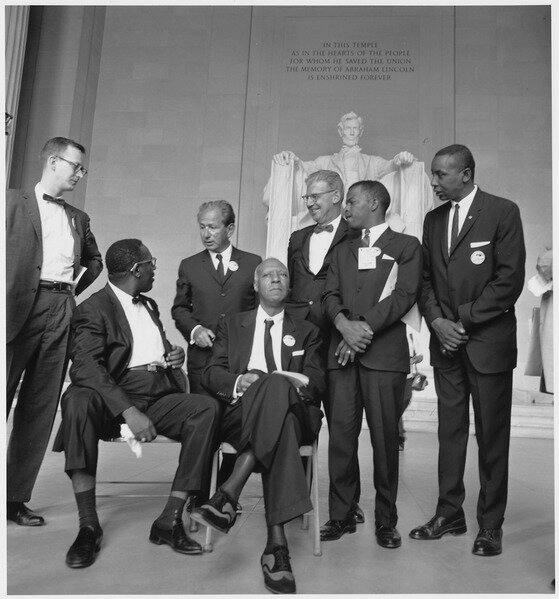

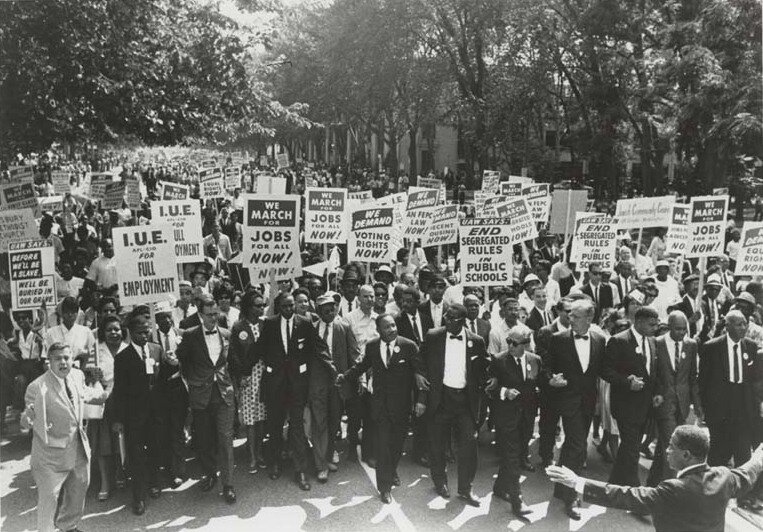

THE MARCH ON WASHINGTON, 1963

The leaders of the march (L to R) were: Mathew Ahmann, Executive Director of the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice; (seated with glasses) Cleveland Robinson, Chairman of the Demonstration Committee; (standing behind the two chairs) Rabbi Joachim Prinz, President of the American Jewish Congress; (beside Robinson is) A. Philip Randolph, organizer of the demonstration, veteran labor leader who helped to found the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, American Federation of Labor (AFL), and a former vice president of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO); (wearing a bow tie and standing beside Prinz is) Joseph Rauh, Jr., a Washington, D.C. attorney and civil rights, peace, and union activist; John Lewis, Chairman, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; and Floyd McKissick, National Chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality.

Rabbi Joachim Prinz once described his political growth, in his own words:

The village in which I was born cannot be found on any map. Even on the most minute maps of Upper Silesia, in the province in which it was situated, it is not even a dot. The name was Burkhardsdorf.

… It was very difficult for me to establish a relationship with the rabbis and the establishment of the Berlin Jewish community. All the rabbis were at least twice my age and looked at me with great suspicion.… Even for this synagogue I was an obstacle.

(pp. 1-72)

I was very outspoken and my lifestyle was quite different from that of the conventional rabbis. Both my political and Jewish convictions were different from the vast majority of the rabbis who had been in Berlin for many years and lived a very rabbinical life. I was not popular with most of them because I was a Zionist…

[But] I was never able to conceive of religion, certainly not of Judaism, as something that could continue to exist in splendid isolation. To me, the isolation of the Jews from the non-Jewish world and all Jewish problems from non-Jewish problems did not seem to be so splendid. I rejected this completely and tried to interpret Judaism in terms of a faith or a civilization that was able, or at least had to try , to supply answers to the problems that beset the people

… For some strange reason, I also was not aware of the problem of black America. Naively I took for granted that blacks were equal, and that in a democracy there was no problem of any kind of deprivation and discrimination. I walked into the black American problem like a child, naive and uninformed, idealistic and even romantic. I knew that many of the black people were poor, but I was not aware of the causes of their poverty.

(p. 73-194)

“I think that it is fair to say that despite all the speeches he had given and all the things he had been involved in – including speeches in Berlin during the Nazi regime – I think in his own feelings that was the most important speech he ever gave. It was that for a number of reasons, not the least of which was his attachment to this country. This was very much an expression of his identity with this country, one he came to as a refugee from Nazi Germany and gave him a home and a place that he was very happy in. Despite the fact that English was not his native language, he was a forceful speaker in English and loved English.

He identified with the civil rights movement from the moment he stepped off the boat from Germany in 1937. He understood very early on there was a direct connection between the plight of African Americans and the Jewish people. He had to be identified with it.”

—Rabbi Prinz’s son, Rabbi Jonathan Prinz, about his father. • Quoted in When Prinz Spoke Before King by Seth Berkman (2013).